Redefining Psychiatric Treatment Using Machine Learning

Machine learning can be used to find neurologically-distinct subtypes of Schizophrenia.

A major issue with psychiatry is that individuals with the same diagnostic label from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) can actually have very different symptoms or deficits: it is common to count symptoms, and then give a diagnosis if the patient reaches passes a “symptom threshold” (this is an oversimplification, but suffices for illustration). You can imagine that using this scheme, two individuals with the exact same diagnosis might have very few overlapping, or in extreme cases, no overlapping symptoms. This is particularly true with one of the most heterogeneous disorders: Schizophrenia.

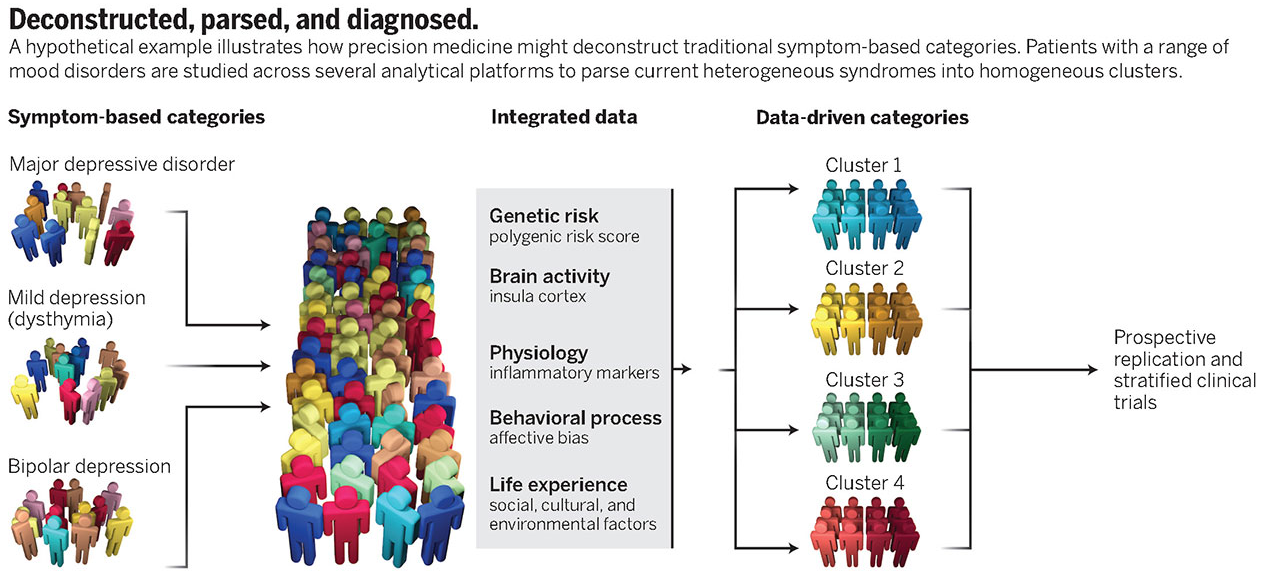

Schizophrenia has many subtypes, and it isn’t clear that it is one disease. Simultaneously with the project on predicting disease trajectory for those at risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, I was helping the lab manage the Social Processes Initiative in Neurobiology of the Schizophrenia’s (SPINS) study. During my 4 years at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, I spent a lot of my time managing the MRI and clinical data collected by the the three hospitals involved in the study. Briefly, the study was designed to explore the neurological underpinnings of social processing deficits seen in some subtypes of schizophrenia. There’s some evidence that the best treatment for Schizophrenia depends on the symptoms, or the subtype, and the optimal treatment varies a lot between individuals. These patterns are largely true for all psychiatric disorders, which led to the Research Domain Criterion (RDoC) framework for mapping genomics and neurological information like brain circuits to behavioural measures in order to generate novel data-driven groups. The underlying goal of the research direction is to understand the brain-behaviour relationships across diseases, to potentially identify neurologically-distinct subtypes of each disease that might be more indicative of the appropriate treatment than the diagnostic label.

In my final year with the team, I ran a preliminary study using the data to evaluate the relationships between the fMRI data collected during the study and the behavioural scores. We focused on social processing scores because they are strong predictors of “functional outcomes”: how well a schizophrenia patient will recover with treatment. Here, social processing includes things like understanding the emotional state or intentions of someone else, things we call theory of mind or empathy.

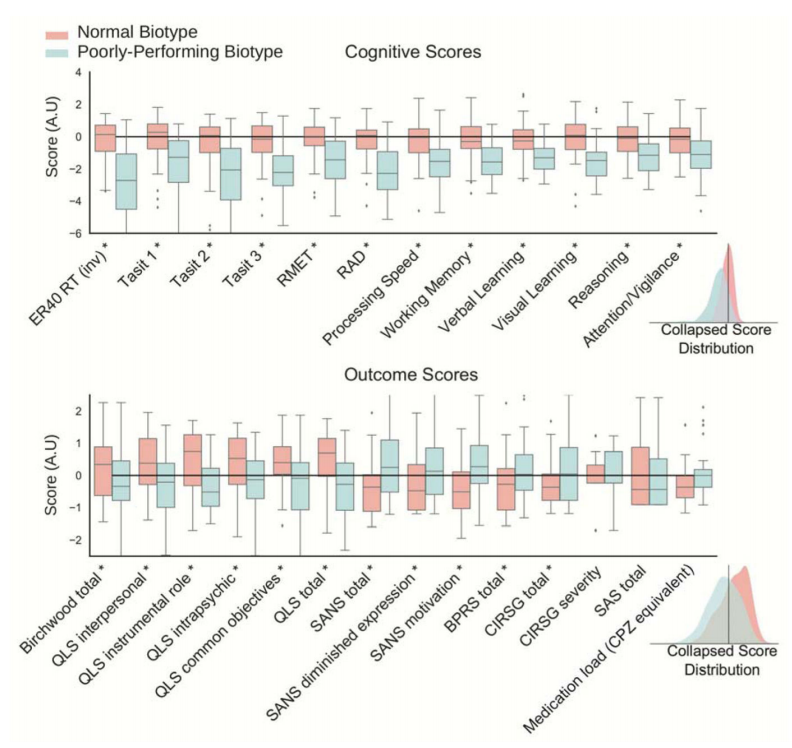

Psychiatric studies are normally conducted by comparing cases (those who meet some DSM criteria) with controls (those who are “healthy”, i.e., don’t meet any DSM criteria). These case-control studies will compare two groups to determine the features that are somehow unique to a disorder. However, we knew that many individuals with schizophrenia have social processing that are similar to healthy controls, and that simultaneously this deficit predicted poor treatment outcomes. This study sought to find subtypes in our sample regardless of diagnosis, by pooling our patients and controls and finding natural groupings of the data based on features derived from both brain connectivity estimates and behavioural scores. We called these subtypes “biotypes”.

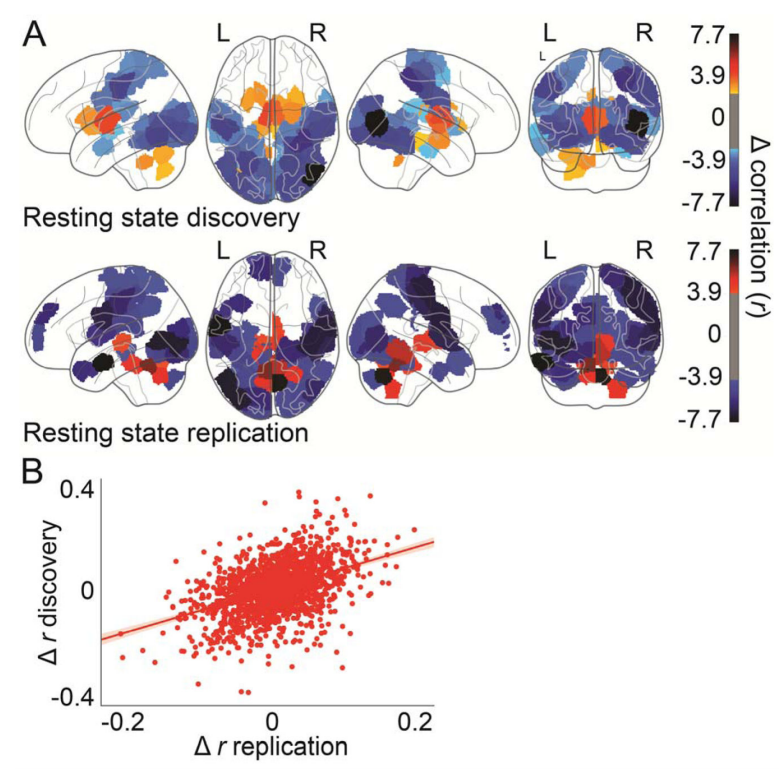

The method employed was straightforward. Due to the small sample sizes, we decided to learn a low-dimensional representation of both the brain connectivity data and the behavioural scores using principal components analysis, and then found pairs of components that were strongly correlated across patients (this approach is known as canonical correlation analysis). These correlated components, which we can call “canonical variates”, were only retained if they were robust in the training set, which we evaluated using cross-validation. The robust canonical variates were finally clustered to generate groups with distinct neuro-behavioural profiles, regardless of diagnosis.

The results were quite striking. A majority of the subjects formed a “normally performing group”, comprised of about almost all of the healthy controls and about half of the patients with schizophrenia. In this group, the behavioural and functional outcome scores of interest were high regardless of diagnosis. The rest of the patients formed a “poorly performing biotype”, and performed significantly worse on these behavioural and functional outcome tests. The difference in these functional outcome scores using a case-control comparison was much smaller than observed when forming the groups according to our biotypes, even though the functional outcome scores were not used at all to derive these new groups.

What was also quite interesting was the neurological differences between these groups. The regions in red (below) are regions with heightened connectivity in the normally-performing biotype, including many subcortical regions with extensive connectivity with frontal regions required to understand others intentions. On the other hand, the blue regions are areas with heightened connectivity in the poorly-performing biotype: these regions are primarily considered early-stage visual processing regions, with less importance in high-order cognitive processes such as understanding the intent of others. A speculative, but interesting, reason for all of this might be that schizophrenia arises from synaptic pruning gone haywire. It is normal and healthy for the brain to remove connections as it develops so that only the most useful and efficient ones survive, and if this process is abnormal, it could lead to abnormal functional connectivity profiles. Crucially, this process might happen differently for each patient afflicted with schizophrenia, and this might leave behind a unique signature that can be used to determine the ideal treatment for each patient.

While our study raises just as many questions as it answers, I do think that the general framework is a useful path forward for transitioning away from the DSM, and I am proud of that contribution. You can read the whole paper here.