You Can't Understand A Deep Learning Model by Watching Where It's Looking

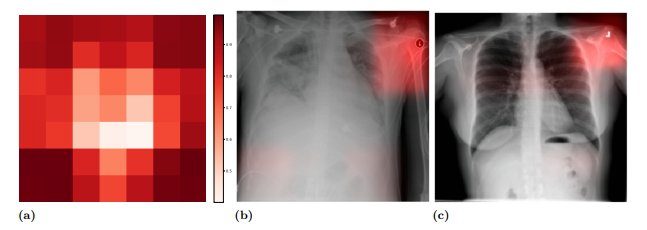

Deep learning’s promise in medical applications are obvious, but it will be hard to get wide acceptance (or regulatory approvals) without doctors being able to understand the “why” behind each prediction. A popular method for doing so is looking at a model’s “saliency” map, which looks like a weather map on top of the image used to make the prediction. The brightest areas are believed to be the regions most involved in the prediction.

This method led to some concern. Take this example, from this excellent paper by John R. Zech et al. In it, we can see that the model is using a metal token that radiology technicians place on the patient (top right hand corner) during image capture to make the prediction (the token helps Radiologists distinguish left from right later on). The issue is when the model notices that people who have a particular kind of token are also more likely to have some disease, say pneumonia, or cardiomegaly (enlarged heart), the model will seem to use the token when making the prediction.

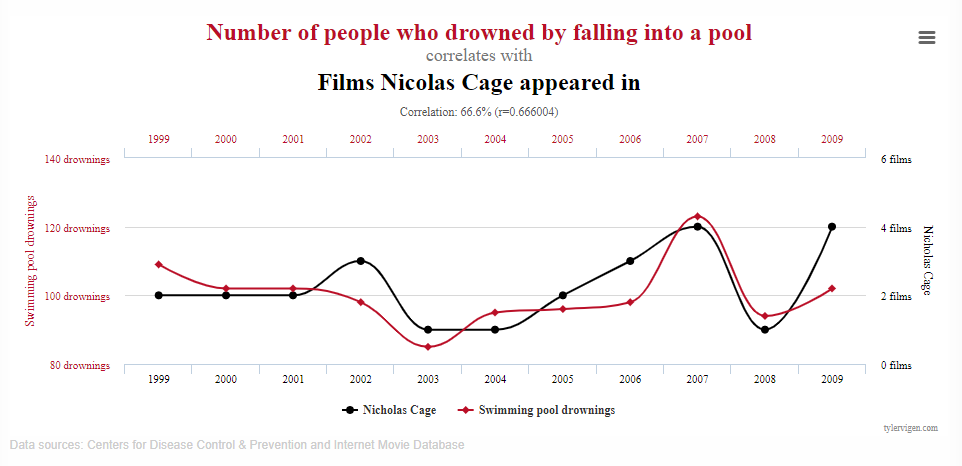

These kinds of relationships are found everywhere, and called “spurious correlations”. The problem with spurious correlations is you can’t rely on them… they might be very high in one dataset, but very low in another, because there is no reason for the two variables to be related at all, and the original correlation was just due to bad luck. Humans are generally good at detecting and discarding these kinds of correlations when they are simple, but very bad at discarding them when the real relationships aren’t immediately apparent. For example, most people would discard this correlation as spurious:

but people often fall for experts who previously predicted some impossible-to-predict event, ignoring the fact that thousands of people were making wrong predictions at the same time and it is possible that this expert might have just been lucky. Very common in finance.

This project was inspired by the above problem. We know where doctors want the models to look for disease, and we can see where the model is looking, so maybe we can directly teach the model to look in the right place, and show that this helps the model generalize to new situations better.

I’m ecstatic that my first publication in a “real” machine learning venue was the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR). I’ll summarize the paper soon. :)